In the 1960s, Tunisia was about to become one of the first African countries to produce electricity from nuclear energy. Carried by a strong scientific ambition and a visionary man, Béchir Torki, This daring project was however brutally interrupted. Back on a peaceful nuclear program as unknown as before-guard.

In the aftermath of independence, Tunisia has an atomic energy police station led by Mohamed Ali Annabi, then taken up by Béchir Torki, nuclear physicist trained in France. At the end of the 1960s, the latter proposed an innovative project: the construction of a nuclear power plant in the south of the country, combining electricity production and desalination of sea water.

The project is not military. It is part of a logic of sustainable development before the hour, meeting two strategic needs: energy independence and access to fresh water in arid areas.

AIAA support and Tunisian ambitions

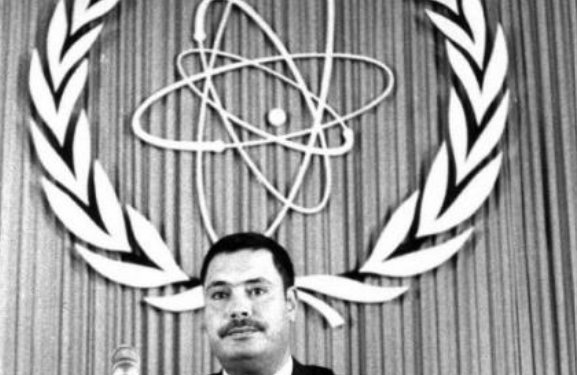

Torki, which will even chair the General Conference of the International Atomic Energy Agency (AIEA) in Vienna in 1969, managed to obtain the technical and moral support of international organizations. He also engages Tunisia in conventions framing the peaceful uses of the atom. Tunisian scientists are trained abroad, and partnerships are sketched, especially with France and the USSR.

At the same period, studies are carried out on the possibility of extracting uranium from Tunisian phosphates, an abundant national resource. This strategic ore could feed a long-term self-sufficient nuclear program.

A brutally interrupted vision

But in 1969, theater: President Habib Bourguiba, influenced by his Minister of Economy Ahmed Ben Salah, decided to abolish the atomic energy police station. The program is stopped without clear explanation.

The reasons advanced vary: cost deemed too high, lack of infrastructure, international diplomatic pressure, or even afraid of too much technological autonomy in a tense regional context.

Torki’s dream collapses, but his work lays the foundations for a scientific tradition. He later founded university laboratories in the fields of nuclear medicine, irradiated agriculture and solar energy. He also publishes several works mixing science and spirituality, such as science and faith, contributing to a reflection on scientific ethics.

His visionary idea of using nuclear to desalt seawater reappears periodically in the debates, while Tunisia faces a double crisis: energetic and water.

And today? The current Tunisian nuclear program remains limited to research and training. However, the memory of Béchir Torki’s project recalls that Tunisia, from the 1960s, had dreamed of great – of a clean, civilian nuclear, and useful to its development.