There are events whose real significance is not immediately revealed. At the time, the arrest of a head of state can seem distant, almost abstract, lost in the flow of international news. Then time acts, the parallels emerge and the meaning appears. The capture of Nicolás Maduro by the United States is part of this logic. It does not yet cause a massive emotional shock in the Arab world or the global South, but it awakens a deeply rooted political memory, made of painful precedents and broken sovereignties.

A painful memory in the Arab world

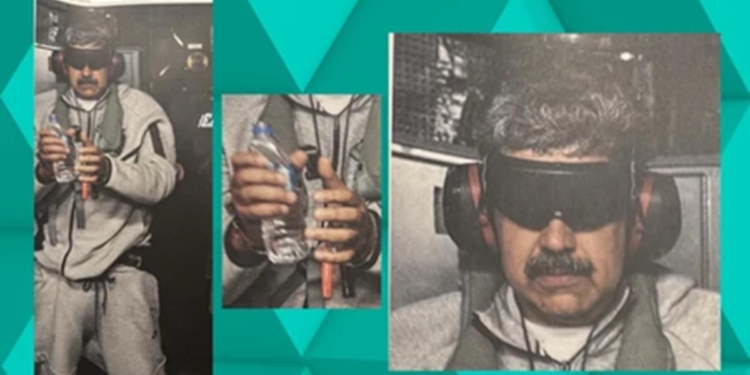

For many Arab countries, the image immediately refers to two founding episodes. In 2003, Saddam Hussein was captured by the American army, exhibited in front of the cameras, tried and then executed. Iraq, for its part, is sinking into chaos for a long time and will never really recover from the brutal disappearance of its state.

In 2011, Muammar Gaddafi was hunted down and then killed after an international intervention presented as an operation to protect civilians. Libya is falling into chronic instability, fragmented between militias and competing powers. In both cases, the fall of man was followed by the collapse of the nation. At the time, the dominant narrative was about liberation. With hindsight, it is the collective humiliation and institutional destruction that dominate the memory.

A global phenomenon, but deeply asymmetrical

Recent history shows that the Arab world and Africa are not the only areas affected by the brutal fall of leaders. In 1989, Manuel Noriega was captured during the American invasion of Panama and transferred to the United States for trial.

In 2001, Slobodan Milošević was arrested by the Serbian authorities under Western pressure and then delivered to the international court in The Hague, where he died in custody. But these cases present a major difference. Neither Serbia nor Panama experienced, after these arrests, a total disappearance of the State comparable to that observed in Iraq or Libya. And above all, Milošević was not captured by a foreign army on his own soil. This distinction nourishes, in the South, the feeling of international justice applied selectively, where force precedes law and where humiliation affects fragile sovereignties above all.

A message to the next leaders

Beyond the Venezuelan case, the arrest of Nicolás Maduro seems to send a broader message to the current and future leaders of the South. It reminds us that contesting the dominant international order, strategic autonomy or breaking with certain alliances can now be paid for by capture, judicial transfer and public staging of the fall. This type of operation therefore aims not only to punish one man, but to warn others, to establish political deterrence by example. Humiliation is never immediate. It reveals itself over time, when promises of reconstruction fade, when institutions disappear and people pay the price for decisions taken elsewhere.

Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi are no longer perceived today only as fallen dictators, but as symbols of imposed collapses from which societies continue to suffer the consequences. With Maduro, whether we like him or not, a new episode is part of this historical sequence, reviving in the Arab world and the global South the same silent concern: how far the normalization of the arrest of leaders as a tool of geopolitical domination will go.

Also read: