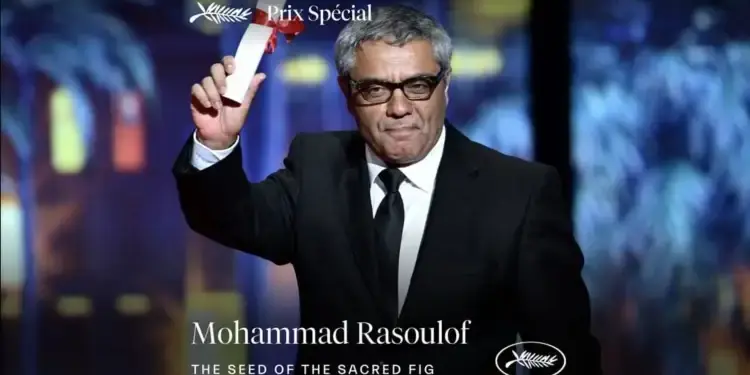

The 77th Cannes Film Festival came to a close the night before last, leaving critics and audiences alike in astonishment. Almost everyone had anticipated that The Seed of the Sacred Fig would take home the Palme d’Or. Yet, the jury chose instead to award it a special prize. Why a special prize? Couldn’t they have at least granted the Grand Prize? It almost feels less like a recognition of the film’s extraordinary craft and more like a nod to Mohammad Rasoulof’s courage—having escaped Iran in secret—rather than an acknowledgment of the film itself, which undeniably deserved the highest honor.

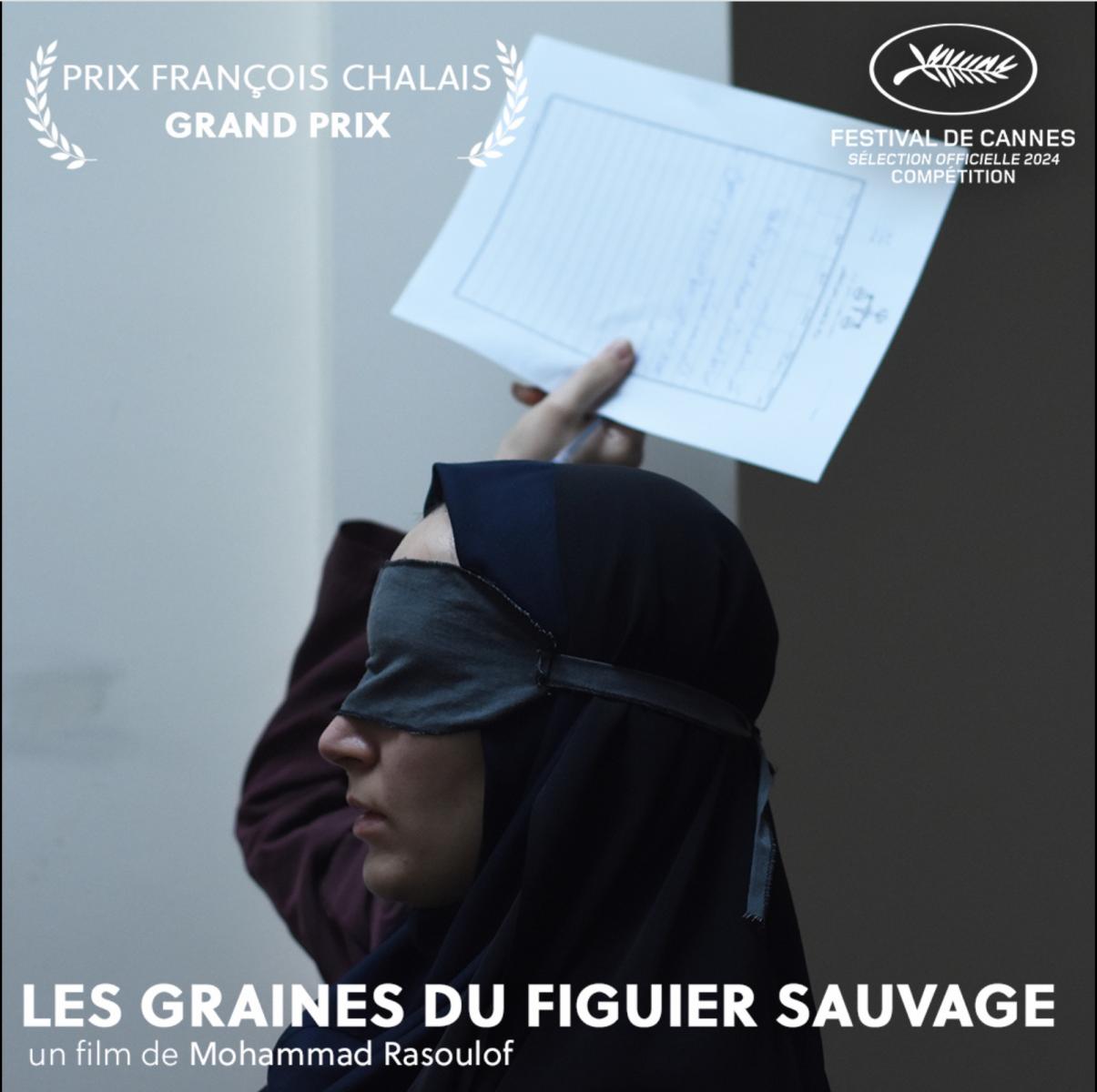

Interestingly, on the same day, the film collected four other awards from different juries: the FIPRESCI Prize, the Ecumenical Jury Prize, the Art Cinema and Experimental Cinema Prize, and the Grand Prix – François Chalais Prize.

For over two decades, Iman (Misagh Zare)—whose name meaning “faith” seems almost prophetic—has served as a civil official, engaged in work that his daughters would likely have been ashamed to know about. Out of loyalty to the system, he receives a promotion—not as a judge, which he had hoped for, but as an investigator, a position few desire. Investigators are tasked with interrogating the accused: young people, artists, political opponents, and those detained for protesting. They also approve death sentences for alleged dissidents. In essence, Iman does more than serve the Iranian regime—he embodies it.

With this intense, contemplative thriller, Rasoulof answers to his own imprisonment in 2022, which came amid protests sparked by the death of Jina Mahsa Amini, arrested and beaten for allegedly wearing her hijab incorrectly. The film explores the tensions gripping Iranian society, seen through the lens of a well-established family in Tehran.

For much of this nearly three-hour film, the narrative revolves around Najmeh (Soheila Golestani), the devoted wife and mother. The Jina revolution marked a turning point for women in Iran, and The Seed of the Sacred Fig portrays the beginnings of a new solidarity—a movement that begins with students but grows when ordinary citizens like Najmeh join the cause.

At first, Najmeh is entirely focused on her husband’s promotion, which promises privileges such as a spacious official residence. She insists that her daughters, Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and Sana (Setareh Maleki), maintain perfect conduct in every respect: behavior, dress, and friendships. She disapproves of their association with Sadaf (Niousha Akhshi), a girl with a freer, less constrained spirit. With their newfound social status, any misstep could bring shame to the family and endanger Iman’s career—a risk Najmeh refuses to accept. While Iman enforces conformity at work, Najmeh imposes it at home.

Yet the daughters begin to see the world outside differently. They witness the consequences of state violence, seeing their friend Sadaf, an innocent bystander, injured by police firing on protesters. Constantly connected to social media, they see footage of violent repression—images Najmeh refuses to acknowledge. She scolds her daughters whenever they show interest, dismissing the videos as false propaganda. Meanwhile, young demonstrators shout, “Down with the theocracy! Down with the dictator!” But Najmeh, faithful to state narratives, sees only disorderly youth. Interspersed real-life footage throughout the film, however, makes the truth undeniable: the police brutality is stark and terrifying.

Cannes 2024 – “The seed of the sacred fig”, Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and Najmeh (Soheila Golestani).

These protest videos—acknowledged by the daughters, rejected by Najmeh—become a central element of the story. They illustrate the divide between those yearning for freedom and those clinging to the status quo, whether out of fear or conviction. The film shows how willful ignorance and systemic repression can coexist within a single family, reflecting the larger tensions of Iranian society. It also underscores the generational gap, the inability of the older generation to understand the younger generation’s demands for basic freedoms: the freedom to reject the veil, dye their hair, or wear nail polish. Najmeh and Iman cannot comprehend these claims. They believe deeply in the regime and the religious precepts upon which it is founded, giving their convictions a frightening sense of righteousness.

Meanwhile, Iman’s promotion begins to corrode him internally. He realizes that his true role is not to investigate cases—cases he barely has time to read—but to approve convictions dictated by others, whether he agrees with them or not.

The situation escalates when his colleague Ghaderi (Reza Akhlaghirad) provides him with a pistol for “self-defense.” This weapon, a symbol of his moral compromise, disappears mysteriously, intensifying Iman’s paranoia.

Who could have taken it? Could it be Sadaf, scarred by police violence? Or perhaps a family member? If so, which of the three women? The loss of the gun threatens not only his career but possibly his freedom. Beyond that, what does it mean for Iman, and why would anyone risk taking such a step?

This turning point transforms the film from a careful character study into a gripping psychological thriller. Iman turns against his own family, forcing them to confront the brutal reality of their lives. In his quest to recover the weapon, he subjects his wife and daughters to interrogations, exposing the viewer to the devastating consequences of state arrests, including the torture endured by young protesters until they confess. Najmeh, confronted by Alireza—a colleague who interrogates her, claiming she is “lucky” because the process is unusually respectful—begins to doubt her beliefs.

The family dynamic shifts. Najmeh, initially a blind supporter of her husband, slowly awakens to the regime’s abuses. Meanwhile, feminist and student movements persist, publishing names and addresses of officials to expose them to the public. Iman himself becomes a target. The man willing to condemn innocents for career advancement begins to panic, revealing how fear and power can transform a person. Once seemingly a devoted husband and father, he becomes increasingly paranoid, dangerous, and selfish, obsessed only with his own survival.

The family home itself becomes a site of terror. Rasoulof’s technical mastery immerses the audience in this oppressive environment. The missing pistol heightens tension, culminating in dramatic sequences where Iman confines his relatives in an old family house, symbolizing the ruins of Iran itself.

One of the film’s most daring choices is portraying Najmeh and her daughters without headscarves indoors. In the tightly controlled cinema of Iran, actresses are expected to be veiled at all times, even indoors. Rasoulof’s decision, first seen in his previous film There Is No Evil, where an actress appears un-veiled inside, enhances the realism and authenticity of the story, while defiantly challenging the regime’s restrictions. At Cannes, the two actresses present were also un-veiled, having clandestinely fled Iran ahead of the festival.

The Seed of the Sacred Fig is more than a film—it is an act of resistance, a powerful testimony to the struggle for freedom in Iran. Filmed in secret, it presents an unflinching vision of the country, with Rasoulof’s courage and determination palpable in every frame.

This film, deserving of the Palme d’Or, is a complete work of art—narratively, visually, and emotionally. It exposes corruption, fear, and repression, while demonstrating the resilience of the human spirit. By focusing on family dynamics, Rasoulof universalizes the struggles specific to his country, making The Seed of the Sacred Fig essential cinematic viewing.

Neïla Driss