Rewatching Man of Ashes (L’homme de cendres) today, in its restored version presented at the 2025 Carthage Film Festival, is far from a simple journey into the past. It is a deeply contemporary experience, almost unsettling in the way the film seems to resist time. Although I have seen it several times since its release, this screening offered a particular pleasure, that of rediscovering a work that unfolds with the same intensity, as if it were being seen for the first time. The restoration plays an essential role in this rediscovery, but it cannot alone explain this sensation: above all, it is the film’s intrinsic strength that remains striking.

Released in 1986, Man of Ashes stands as a foundational work of modern Tunisian cinema. Through the character of Hachemi, a young man on the verge of marriage, Nouri Bouzid explores the consequences of a sexual trauma suffered in childhood, long buried yet reawakened as adulthood approaches a decisive turning point. The film moves directly into its most sensitive territories, laying bare mechanisms of silence, shame, and repression within a society where unspoken truths often weigh more heavily than words. The narrative avoids effects or didacticism, opting instead for a direct and at times uncomfortable approach that forces the viewer to confront a reality rarely depicted on screen at the time.

Upon its release, Man of Ashes triggered a genuine shockwave. The film sparked considerable controversy precisely because it confronted subjects that were largely absent—or outright forbidden—in Tunisian and Arab cinema: pedophilia, sexual abuse, violence against children, and the lasting traumas that result. The film did not skirt these issues or cloak them in suggestion. It exposed them with a bluntness that unsettled and at times shocked, revealing the deep resistance of a society reluctant to face certain wounds. This controversial reception speaks as much about the film as it does about the context in which it emerged.

As early as 1986, however, Man of Ashes was recognized well beyond Tunisia’s borders. The film was selected for the Cannes Film Festival in the Un Certain Regard section, confirming the singularity of Nouri Bouzid’s vision and the significance of his cinematic gesture. That same year, it won the Tanit d’Or at the Carthage Film Festival, securing its place in the history of Tunisian cinema. This dual recognition—international and regional—cemented The Man of Ashes as a major work, simultaneously acclaimed and debated, admired and unsettling.

Forty years later, it is clear that the film’s subject matter has lost none of its relevance. Sexual violence against children and the traumas it engenders continue to exist today, including in so-called developed societies. In this sense, Man of Ashes requires no artificial updating to remain meaningful. It still speaks in the present tense, without the distancing effect of age or historical framing. This enduring relevance largely explains why the film continues to resonate so powerfully.

From a formal standpoint, the film’s modernity remains striking. Nouri Bouzid’s genius lies precisely in his ability to anchor his work outside of time. The direction is rigorous and tense, stripped of any superfluous effects. Framing, rhythm, and close attention to silences and bodies build a sustained tension, never tipping into sensationalism. The film does not seek to shock through excess, but through the precision of its gaze. Even forty years on, it never feels formally outdated.

Within Nouri Bouzid’s career, Man of Ashes occupies a central position. From this first feature, the filmmaker asserts a clear approach: using cinema as a space for confrontation with unspoken truths, where individual wounds reveal collective fractures. Bouzid establishes himself early on as an uncompromising auteur, choosing to face society’s darker zones rather than sidestep them. The film already outlines the major themes that would mark his later work, shaped by a constant interrogation of the body, violence, freedom, and social constraint.

In 2025, Man of Ashes underwent a complete restoration, marking a decisive stage in the film’s rediscovery. The project was carried out jointly by the Cineteca di Bologna, the Royal Belgian Film Archive (Cinematek), Cinétéléfilms, and the Ciné-Sud Patrimoine association, with the support of Tunisia’s Ministry of Cultural Affairs. The technical work included 4K digitization of the original negative, along with image and sound restoration, undertaken in specialized laboratories such as L’Immagine Ritrovata.

This restoration goes beyond a simple act of preservation. It restores the image’s texture, the depth of the frames, the contrasts, and the film’s sonic richness with renewed precision, fully honoring the mise-en-scène and the careful attention paid to everyday details. It refreshes the viewer’s perspective and strengthens the film’s ability to engage in dialogue with the present.

The restored version of Man of Ashes was unveiled for the first time at the 39th edition of Il Cinema Ritrovato in June 2025, in the Cinemalibero section. This festival, internationally recognized for its work in preserving and transmitting cinematic heritage, provided a particularly meaningful setting for the film’s rediscovery. This international premiere repositioned Man of Ashes within a global history of restored cinema, ahead of its presentation to Tunisian audiences and its screening at the 2025 Carthage Film Festival.

Forty years on, Man of Ashes also stands as a valuable testimony to social practices and traditions that have largely disappeared. The film does more than tell an intimate story: it preserves traces of a way of life, a family structure, and collective rituals that now belong to memory. It depicts a Sfaxian family borj where the entire family gathers to prepare for a wedding, as was customary at the time, over a long, shared period in which everyone played a clearly defined role. This space—both domestic and communal—becomes the film’s beating heart, a site where bodies, words, and gestures constantly circulate.

Filmed without emphasis, with sustained attention to the details of daily life, these scenes now take on an almost documentary value. They reveal an extended family organization, a way of living together and preparing a collective event that contrasts sharply with the more fragmented and individualized forms of contemporary life. The film records these gestures without commentary or idealization, simply granting them the time and space needed to exist on screen.

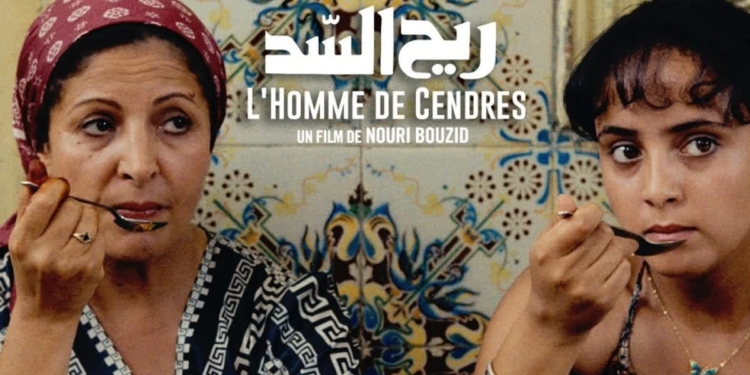

We see women at length preparing the hlouw, traditional pastries inseparable from major celebrations, in collective labor where gestures are repeated, transmitted, and shared. This preparation is not merely culinary; it is social, almost ritualistic. The women gather, talk, and work, inscribing their activity within a generational continuity. The film also shows the extended family gathered around a mida and a senia, the low round table around which a shared dish is eaten. This communal meal, taken close to the ground, conveys a particular vision of conviviality, family bonds, and togetherness that has largely disappeared or become marginal today.

At the same time, the men are busy preparing the space for the celebration. They stretch tents using green tarps, organize the area, move objects, and arrange the outdoor space to welcome guests. These precise, repeated gestures reflect a division of roles that structured social life at the time. Nothing is presented as folkloric; everything is simply there, filmed in its normality and self-evidence. Yet forty years later, that self-evidence has vanished. These practices, ways of doing things, and collective rhythms are now almost forgotten, and younger generations often know them only through fragments, stories, or old images.

Through these scenes, Man of Ashes far exceeds its status as fiction to become a true visual archive of a world in the process of disappearing. The film’s restoration restores full clarity, depth, and texture to these images, further reinforcing their memorial dimension. What the film shows of the past is not frozen; it is a living past, filled with gestures, voices, and presences that cinema allows us to encounter once again.

The film also preserves the memory of a form of coexistence that has since become fragile. The presence of Yacoub Bchiri, who performs a song in the film, embeds popular music within the very fabric of the narrative. Through its locations and characters, the film evokes a time when apartment buildings housed residents of different faiths, living side by side without religion serving as a central marker of identity. This everyday coexistence, filmed without discourse or demonstration, now appears as a precious testimony to a social reality once taken for granted.

Finally, the screening highlights the strength of the cast. Several actors who would later become recognized figures in Tunisian cinema appear here early in their careers. More striking still is the fact that the two lead actors have since disappeared from the screen, leaving behind performances that remain inseparable from the film’s identity.

Rewatching Man of Ashes today is to recognize how certain works traverse time without erosion. It is also a reminder that cinema can be a space of speech, memory, and transmission. The presentation of this restored film at the 2025 Carthage Film Festival is not merely an act of homage; it affirms the necessity of continuing to screen and question a cinema that, forty years later, still says what others prefer to leave unspoken, while preserving the trace of a world that has largely vanished.

Neïla Driss