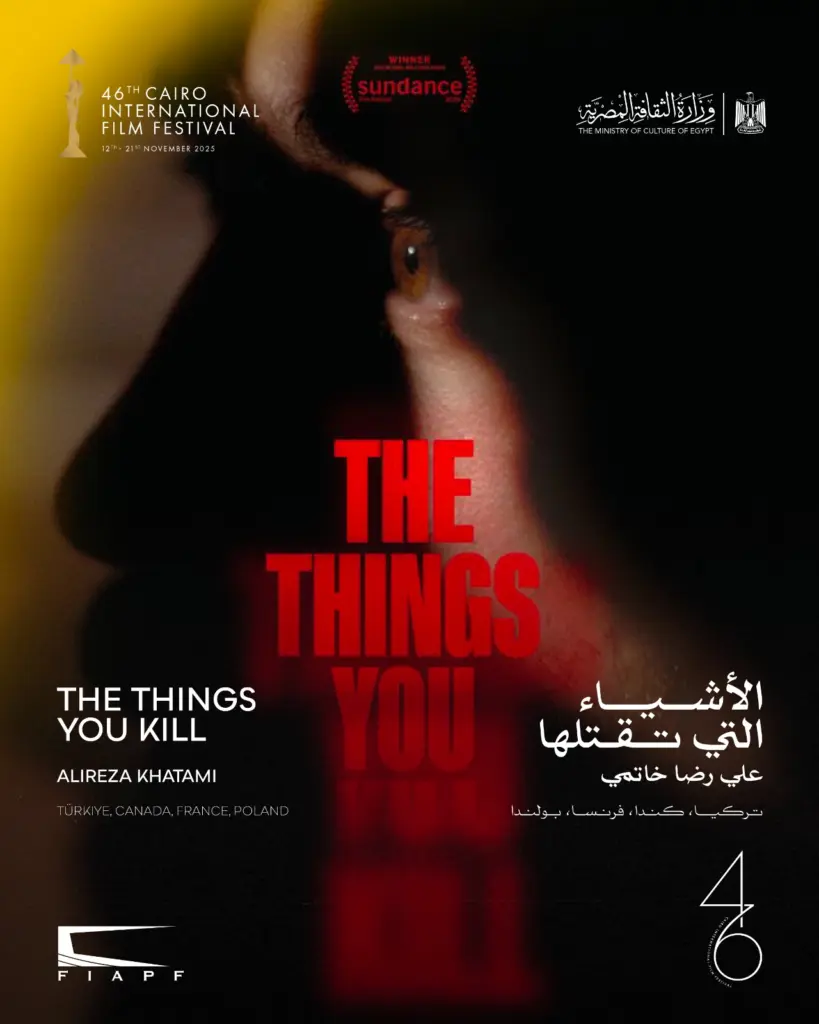

In The Things You Kill (Turkey, Canada, France, Poland | 2025 | 113 min), selected for the International Competition at the 46th Cairo International Film Festival and chosen as Canada’s official submission for the Best International Feature Film Oscar, Alireza Khatami delivers a work of remarkable emotional precision — poised between psychological drama and existential thriller. Known for Oblivion Verses, in which he explored collective memory and the scars left by political violence, the Iranian filmmaker turns his gaze inward, examining guilt, inheritance, and the fragile thread connecting generations. Here, everything narrows to a house, a mother, a father, and a son trapped in a past that refuses to fade.

Ali, a literature professor who has settled in Turkey after years in the United States, appears to lead a peaceful life. His days unfold between his classes and the garden he tends with quiet dedication. Yet that surface calm conceals a buried history: a domineering father, a mother who withdrew into silence, and a son who learned early to speak through restraint. When his mother dies under circumstances that remain unclear, the tenuous balance of his life shatters. Returning to his childhood home, Ali encounters a presence that unsettles him — Reza, a gardener he hires almost by chance. Reza’s arrival marks the beginning of a subtle disturbance. He is not merely a helper but a silent witness, perhaps even a mirror in which Ali begins to glimpse what he has spent years refusing to confront.

Khatami constructs the film as a slow, immersive descent into memory. The narrative moves through fragments — objects heavy with meaning, gestures that speak more than dialogue, silences that throb with withheld emotion. Each moment draws Ali back to his mother, and to the father whose violence shaped him as much as it scarred him. The film’s core tension lies there: between tenderness and cruelty, the yearning to love and the fear of repeating the damage one has inherited.

The story deepens when we learn that Ali, in the midst of trying to conceive a child, is himself on the verge of fatherhood. This gives new weight to every choice he makes. His reckoning is no longer about understanding the past but about breaking the chain that links it to the future. As he draws closer to the truth surrounding his mother’s death, he becomes aware of another kind of danger — not the violence already done, but the violence waiting to be passed on. The film becomes a dialogue across generations: the father he could not love, the mother he could not save, and the child he hopes to bring into a world still governed by silent cruelty.

The notion of revenge that underpins the film is not directed at a single person. It is aimed instead at a structure — a patriarchal system of domination, silence, and fear. Khatami’s film is less about retribution than about recognition: the moment when a man realizes that the violence he despises is also inside him. Through Ali’s journey, Khatami questions what it means to be a man in a culture where strength has long been confused with brutality and where sensitivity is treated as a flaw. The cultivated professor, the dutiful son, the rational thinker discovers that he, too, carries the imprint of a legacy he thought he had escaped. What he tries to “kill” are the reflexes of patriarchy, the wounds inflicted on the women in his family, and the paralyzing guilt of having remained silent.

Visually, The Things You Kill unfolds with hypnotic precision. Khatami films the family home as if it were the inside of a mind — each room a repository of memory, each corridor a passage through guilt. The camera lingers on the smallest gestures: a hand brushing a wall, a breath caught in hesitation, a shaft of filtered light crossing a face. The subdued palette, the soft lighting, and the deliberate pacing evoke a world where truth appears only in half-light. Nature, too, becomes a participant in the drama. The garden, a recurring motif, mirrors Ali’s psychological excavation — a place of labor and renewal, where he digs into the soil as though unearthing his fears and burying them again in an attempt at purification. Reza, in this context, is not a mere gardener but the embodiment of quiet awareness, a living conscience observing what Ali cannot yet name.

The strength of Khatami’s film lies in how it interlaces the personal and the political. Without overt statement or manifesto, it examines how social structures mold masculine behavior and perpetuate unseen forms of violence. The mother’s death functions as both rupture and revelation — it frees a long-suppressed voice yet exposes the near impossibility of undoing inherited patterns. Khatami’s gaze remains compassionate but unsparing; he refuses to moralize, preferring instead to watch, with patience and precision, the contradictions of a man torn between love and shame, memory and forgetting.

Ekin Koç delivers a performance of striking restraint. His stillness, his silences, carry the emotional gravity of someone unable to articulate pain. Across from him, Erkan Kolçak Köstendil gives Reza an enigmatic calm that suggests both empathy and judgment. Together, their interactions — often sparse, always charged — take on a spiritual weight. These are not simply conversations but confrontations between conscience and denial, lucidity and submission. Khatami’s spare direction heightens this tension; each pause feels deliberate, each silence like the echo of something irretrievable.

As the film draws to its close, realism gradually dissolves. The boundary between memory and perception blurs, and what remains is not the external world but the landscape of a man seeking peace. The Things You Kill turns into a meditation on responsibility — on whether one can truly be free without acknowledging what has been destroyed. Its title carries multiple meanings, suggesting that what we kill — in ourselves or in others — inevitably shapes who we become.

Alireza Khatami delivers a film of remarkable unity, both sensory and intellectual, lyrical yet rigorously structured. He transforms pain into knowledge and guilt into awareness. Demanding but deeply human, The Things You Kill invites the viewer to descend with Ali through layers of silence and suppressed memory. When the truth finally emerges, it offers neither consolation nor absolution — only the difficult clarity of living with what has been killed: within oneself, within others, and within history.

Neïla Driss