Making a film about Oum Kalthoum is never a neutral act. It means engaging with a figure who far exceeds the artistic sphere and belongs instead to collective memory, to the intimate, to something almost sacred. Oum Kalthoum is not merely a legendary singer: she is a constant presence, passed down from one generation to the next, a voice intertwined with family memories, life moments, and endless nights. To portray her on screen is, from the outset, to accept that the film will be judged not only as a work of cinema, but as a statement—perhaps even as a symbolic gesture.

It is within this particularly sensitive context that El Sett was conceived, an ambitious film devoted to Oum Kalthoum. Premiering as a world premiere at the Marrakech International Film Festival, the film immediately established itself as an event, even before its theatrical release. Not only because of its subject, but also because of the scale of the project, its substantial budget, and its stated ambition to deliver a cinematic fresco commensurate with the magnitude of the myth.

Its director, Marwan Hamed, has occupied a central position in contemporary Egyptian cinema for several years. From The Yacoubian Building, which marked a turning point in the Egyptian cinematic landscape, to large-scale productions that became major public phenomena such as Kira & El Gin, his career has established him as a filmmaker capable of combining narrative scope, visual ambition, and wide audience appeal. Within this trajectory, El Sett fits logically: a film carried by a director accustomed to collective narratives and emblematic figures, and fully aware of what it means—symbolically and culturally—to bring an icon like Oum Kalthoum to the screen.

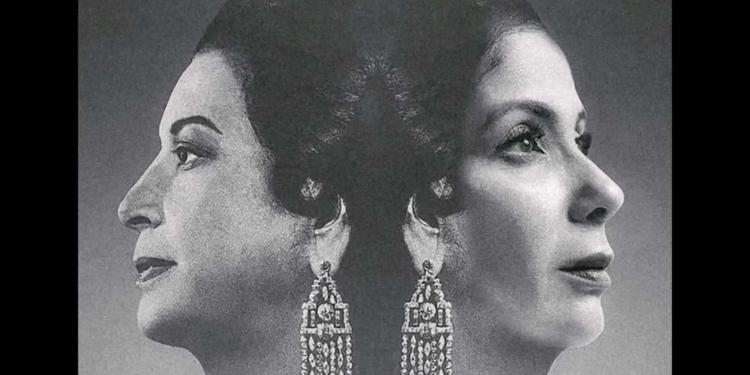

Even before filming began, El Sett sparked its first controversy, the most immediate and predictable one: the casting of Mona Zaki as Oum Kalthoum. The debate emerged very early on, before any images were released, before any screening, fueled by a question as simple as it was insoluble: how does one embody Oum Kalthoum? After the television series Oum Kalthoum, in which Sabreen delivered a performance that became foundational in the popular imagination, any actress inevitably faced an overwhelming comparison. Sabreen had become Oum Kalthoum for an entire generation. Yet it was unthinkable to cast the same actress in the film, precisely to avoid any confusion or interference between the series and the cinematic project.

So who could be chosen? Mona Zaki became the focal point of the criticism, but the debate extended far beyond her. One can reasonably assume that whatever the choice—Menna Shalaby, Amina Khalil, Hend Sabry, or anyone else—the controversy would have existed regardless. No actress could ever be “perfect” when confronted with such an absolute figure. Mona Zaki did what she could, with her tools, her sensitivity, and her limitations. She convinced some viewers, and not others. And that outcome seemed inevitable from the very beginning.

After the first screenings, a second wave of criticism emerged, this time centered on the portrayal of Oum Kalthoum offered by the film. Some reproached El Sett for depicting her as too harsh, too authoritarian, too concerned with power or money—traits perceived as demeaning for a national icon. Showing her as a smoker, demanding, sometimes inflexible, was seen by some as an attack on her image, as though Oum Kalthoum could only be represented in an idealized, irreproachable, almost abstract form.

Paradoxically, other criticisms argued the exact opposite. El Sett was also accused of overly smoothing its subject, of avoiding uncomfortable territory, of keeping its distance from sensitive issues. The film does not address Oum Kalthoum’s jealousy, does not evoke rumors surrounding her alleged involvement in Ismahan’s death, and does not depict her initial opposition to Abdel Halim Hafez. It makes no reference to rumors about her sexuality and offers not the slightest suggestion of sexual ambiguity. None of this is addressed, even indirectly. Silence is absolute on these matters.

This contradiction is revealing. How can a film be accused of damaging Oum Kalthoum’s image while simultaneously being reproached for protecting it too much? El Sett thus finds itself caught in an insoluble tension, expected to say everything without ever unsettling, to humanize without ever desacralizing.

Another controversy concerned the use of archival footage. Some viewers felt that its repeated presence occasionally gave the impression that the film was drifting toward documentary, at the expense of fiction. Personally, I experienced the exact opposite. These materials—posters, newspaper clippings, archival images layered over the narrative—deepened my immersion. They give the film a particular density, reminding us that what is being shown truly happened. Oum Kalthoum truly wore these clothes, truly occupied these spaces, truly lived these events. Far from breaking the illusion, the archives give it greater scope. The reconstruction of sets and costumes works in the same direction, anchoring the film in tangible reality. That requires a substantial budget, and the film clearly had one. This visual ambition is one of its strengths.

The film was also criticized for featuring numerous major Egyptian film stars in small roles or cameos. Here again, this is a directorial choice. Perhaps Marwan Hamed wanted to create a collective showcase, a shared tribute, bringing together multiple figures of Egyptian cinema around Oum Kalthoum. Personally, these appearances did not bother me. Their absence would not have been noticeable either. They are not necessary, but they do not harm the film.

It was therefore with all these controversies in mind that I went to see El Sett. And yet, from the very first minutes, the magic took hold. The film opens with the historic Olympia concert in November 1967. Outside the Paris theater, the crowd gathers. Spectators from Europe, North Africa, the Gulf countries—and sometimes even farther afield—wait for Oum Kalthoum. I immediately felt as though I were entering the hall with them, and through that, entering the film itself, as if I were at the Olympia, among a crowd shouting “Souma, Souma,” intoxicated with happiness at the idea of finally encountering Kawkab El Sharq.

This concert is a historic moment, not only for Oum Kalthoum, but for the Olympia itself, which had never experienced such a phenomenon, neither before nor after her. Watching these scenes, I was reminded of the many interviews with Bruno Coquatrix, then director of the Olympia, describing his astonishment at the scale of the success, his amazement at a crowd that had come from everywhere, from all social classes and all religions, united by the same fervor. This long-established memory undoubtedly intensified my immersion. Very quickly, emotion took over. On several occasions, I struggled to hold back tears.

Of course, El Sett skims over an immense and intense life. Three hours cannot contain such a destiny. But what the film shows is essential: a woman who emerged from a remote village in the Egyptian countryside, endowed with a great voice, but above all with courage, intelligence, and a keen understanding of the world around her. A woman who knew how to negotiate, seize opportunities, learn, and cultivate herself. A woman who, beyond music, created a magazine, wrote in it, asserted a female point of view, and managed to preside over a union. All of this in the 1920s, 1930s, and beyond, at a time when the majority of Arab women were still confined to the domestic sphere.

All these debates, however, tend to obscure the essential point: El Sett ultimately needed to succeed at one fundamental thing—eliciting emotion. And as far as I am concerned, that mission is fully accomplished. By its very subject, this film could never please everyone. Oum Kalthoum belongs to our collective memory, and each of us carries her differently. Everyone has their own image, their own memories, their own expectations. Everyone would have wanted to see certain things told, and others left aside. There are undoubtedly a thousand and one ways to make a film about Oum Kalthoum, and all of them would be debated, debatable, and contested. Marwan Hamed made his choices. He has his approach. One either embraces it or does not. I did. I embraced it for the emotion he managed to create, for the testimony he conveyed. And ultimately, is emotion not what matters most when speaking of a film about Oum Kalthoum?

At one point, another question imposed itself on me, almost despite myself: that of the external gaze. Can El Sett travel? Not in an industrial sense, but in a sensitive one: can this film touch audiences who do not know Oum Kalthoum, who did not grow up with her voice, who do not carry within them the memory of nights suspended by her songs, who do not instinctively grasp what her name represents in the Arab imagination? I found myself thinking about this because, for me, the film’s emotion stems not only from what it tells, but from what it awakens. It activates a preexisting memory, a familiarity, a transmitted history, sometimes even a form of intimate recognition. This deeply cultural and affective dimension is likely both the film’s strength and one of its potential limitations outside its natural context.

I cannot speak on behalf of a foreign spectator. I do not have that distance, and I do not claim to. But I wonder what El Sett would become if it were seen as one discovers an artist for the first time: a woman from a village who became a star, crossing eras, stages, and social transformations. Would one feel the same fervor, the same density, the same vertigo? Or would the film provoke something else—curiosity, admiration, perhaps distance, perhaps even astonishment at the quasi-religious intensity it portrays? The question remains open. It does not diminish my experience; on the contrary, it underscores it, reminding me that, in my case, El Sett does not merely recount a legend—it engages in dialogue with a living memory.

The controversy surrounding El Sett ultimately says as much about our relationship with Oum Kalthoum as it does about the film itself. It is reproached for both showing too much and not showing enough, for humanizing and smoothing, for betraying and sanctifying. This contradiction reveals a deeper difficulty: how does one represent on screen a figure who has become, for many, untouchable?

El Sett is neither an encyclopedia, nor a tribunal, nor an absolute hagiography. It is a situated, assumed perspective. One may discuss its choices, regret some, defend others. But the film manages to achieve something essential: giving flesh to an extraordinary trajectory, that of a woman who, in a world largely hostile to her, claimed her voice, occupied space, exercised power, and durably marked the cultural and political history of the Arab world.

Perhaps this is the most compelling question raised by El Sett: not what it says or does not say about Oum Kalthoum, but what we are willing—or unwilling—to see when a myth steps down from its pedestal and enters the realm of cinema.

Neïla Driss