A Journey Through Festivals

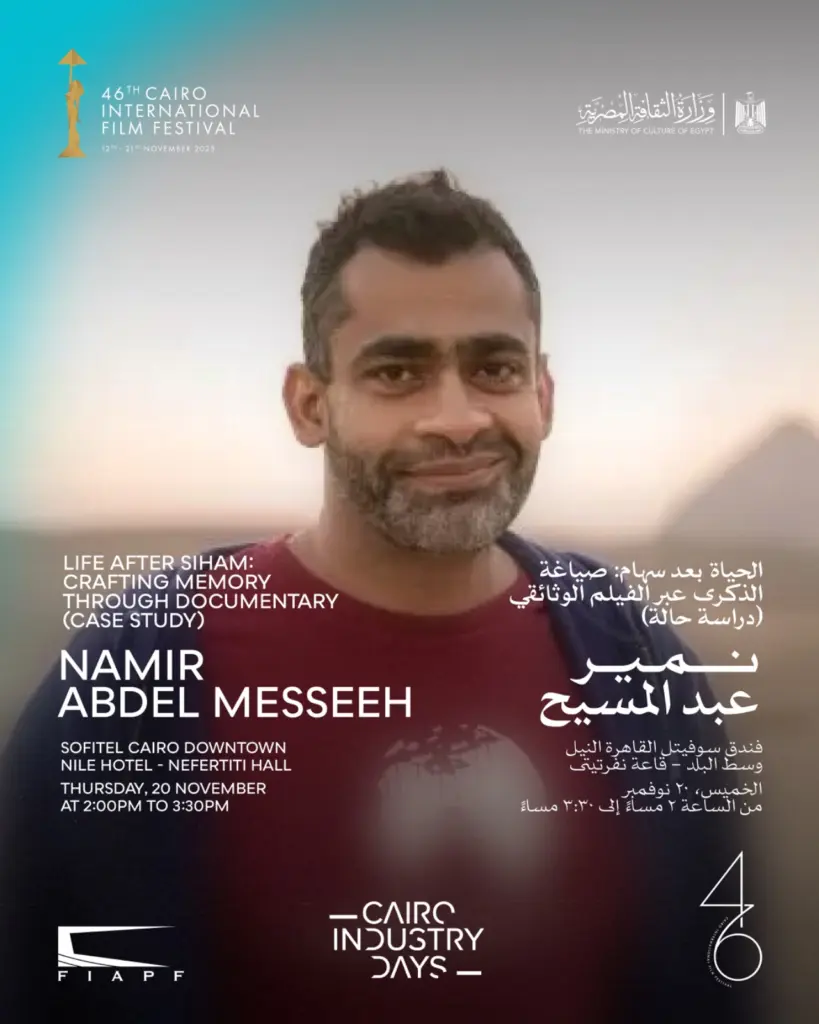

First presented at Cannes in the ACID selection, Life After Siham by Namir Abdel Messeeh has since embarked on a long international journey. Upon arriving in Egypt, at El Gouna, the film won two awards — Best Documentary and Best Arab Documentary — before being screened out of competition at the 46th Cairo International Film Festival (November 12–21, 2025), in the “Special Screenings” section.

From a Childhood Between Paris and Egypt to a Deeply Personal Body of Work

This profoundly personal film — part mourning diary, part gesture of fidelity, part exploration of memory — extends the trajectory of an artist who, from his very beginnings, has constantly probed the frontier between life and cinema. Born in Paris in 1974 into a Coptic Egyptian family, and trained at La Fémis, Namir Abdel Messeeh has always sought to make his two worlds — France, where he grew up, and Egypt, whose memory he carries — speak to one another.

You, Waguih and The Virgin, the Copts and Me: The First Stones of a Triptych

After his short film You, Waguih (2005), devoted to his father, Abdel Messeeh gained attention with The Virgin, the Copts and Me (2011), which premiered at Cannes in the ACID section and won the Silver Tanit for Documentary at the Carthage Film Festival in 2012. Blurring the line between documentary and fiction, that film already raised the questions that would shape all his work: how to film one’s loved ones, how to make cinema with them — without betraying or confining them.

Filming His Own to Explore Faith, Cinema, and Inheritance

In The Virgin, the Copts and Me, Abdel Messeeh was already filming his own family. Traveling to his parents’ village, he examined stories of apparitions of the Virgin Mary while filming his mother, uncles, aunts, and the villagers. In trying to understand these phenomena, he created a film that was at once spiritual, funny, and lucid — blending religious inquiry with reflection on cinema itself. Mixing documentary and re-enactment, seriousness and humor, he was already staging himself, questioning his place as filmmaker, son, and heir. This intimate gesture, where self-irony meets tenderness, foreshadowed Life After Siham.

Life After Siham: A Story of Grief and Transmission

This new film follows that same path. Eight years after the death of his mother, Siham, and later his father, Waguih, the filmmaker faced a double bereavement and a promise: to tell their story. From that vow came a film about memory and transmission, in which Abdel Messeeh weaves together archival images, footage shot in Egypt and France, and excerpts from Youssef Chahine’s films to craft a narrative both intimate and universal.

In Cairo, the Emotion of a Symbolic Homecoming

During the screening in Cairo, emotion filled the air. For Namir Abdel Messeeh, showing this film in his parents’ homeland carried deep resonance: “It was the first time I saw the Arabic version of Life After Siham with an Egyptian audience, and it was stressful for me,” he confided. “Each screening has been different — in Egypt, Spain, Germany, France… every time the reactions changed.”

He recalled: “In Cairo, the audience applauded several times, right in the middle of the film. That had never happened elsewhere. In Germany, people told me they liked it, but their emotions were more contained. That’s the strength of cinema: each screening has its own life, shaped by the place, the size of the theater, the number of viewers.”

This Cairo screening — among compatriots, friends, and family — had the power of a symbolic return. “I was born in France, but I am Egyptian. My father and mother remained Egyptian even after emigrating to France. They never renounced their Egyptian identity, even though they were buried there. And I am Egyptian too. That’s why I wanted to tell this story, this hadouta masreya (a nod to Youssef Chahine!).”

A Conversation with Film Students: Why and How to Film?

After the screening, the filmmaker led a discussion titled Life After Siham: Crafting Memory Through Documentary (Case Study), aimed primarily at film students, in which he delivered a rich, humorous, and moving testimony about his relationship to cinema, to his parents, and to himself.

From Unsatisfying Shoots to Discovering His True Subject

“I studied film in France and during my studies I made films, but I was never happy with them. I realized a film must say something about you. Mine said nothing about me.” This realization, both simple and decisive, marked a turning point for him.

He recalled his beginnings: “Even after school, I made a short film, but I was still unsatisfied. I felt that while shooting, I had forty people around me whom I didn’t know. I had spent time writing a script, and suddenly I was surrounded by strangers, as if they were stealing something from me. I understood that I needed to film people I loved, people I knew.”

This awareness changed his entire perspective: “I stopped asking myself, ‘What do I want to tell?’ and started asking, ‘Who do I want to film?’ The answer came instinctively: I wanted to film my father.”

Filming the Father: A Refusal, Ten Months of Pleading, and a Film About a Relationship

His first film about his father was born almost by accident. “I had submitted a project to a competition and forgotten about it. One day I learned I had won a €10,000 prize, on the condition that I deliver the film within a year. I wanted to make a thirty-minute short documentary. My father refused. He didn’t understand why I wanted to film him.”

Ten months of discussion and pleading followed. “I had to beg him. Then I realized I had to find a way to film someone who didn’t want to be filmed. The only solution was for the film to be about both of us — our relationship in front of the camera. I had to be there to reassure him.”

That decision gave birth to a new kind of film: not a portrait, but a conversation. Cinema became a way to rebuild a bond. “That’s when I understood that cinema could be a means to love, to understand.”

His mother, upon learning of the project, didn’t hide her jealousy. “She said to me: ‘Why him and not me?’” he recalled with a smile. That remark, both funny and sincere, became the starting point for another film — and for a reflection on how to film those one loves.

An Educated Father, Cinematic Disagreements, and a Founding Tear

“My relationship with films is more important than with human beings. A film speaks, a film communicates, a film is emotion… a film is alive.”

It was at that precise moment that he discovered what a filmmaker truly is: “That’s how I realized there is someone called the director. He’s the one who tells the story. Why and how? A film is the portrait of its director. That’s what made me love cinema.”

Abdel Messeeh often speaks of his father with admiration. “My father was very cultured: he read a lot, went to the theater, to the cinema. But we didn’t like the same films.”

This difference in taste nourished their exchanges — and sometimes their disagreements. “He didn’t like The Virgin, the Copts and Me. He couldn’t understand making a film about one person, or a family, or how that film could win awards.”

Yet it was a silent scene with this reserved, cultured father that became the heart of his inspiration. “On the day of his retirement, he was supposed to give a speech. He couldn’t. A colleague spoke in his place. I had started filming our family and all our gatherings very early on. That day, I was there, filming the celebration. And I filmed a tear that ran down his cheek. That’s when I understood I wanted to make a film so that he could finally say what he had never said.”

The Fear of Ridicule and the Decision to Assume His Family Onscreen

While preparing The Virgin, the Copts and Me, as he was about to film his family in their village, the director decided to call his mother via Skype. “I asked my crew to film the conversation without her noticing. She was asking many questions. When she learned I was going to film the family, she got angry. She said she would tell them to refuse to be filmed, that she would even sue me if necessary.”

“I didn’t know what to do — and I looked at the cameraman, who was laughing.”

That moment, both funny and tense, revealed a buried fear. “My mother was afraid people would mock her family — their poverty, their ignorance.” Watching the rushes later, he realized that this fear itself was a subject, and decided to keep the scene in the film. “I took that responsibility and accepted the audience’s reactions. Maybe some laughed at them, maybe some hated them, but others loved them — because they felt that I loved them.”

For him, filming someone is above all a matter of love. “I asked Yousry Nasrallah if he loved his actors. He answered: ‘Yes, like a father.’ That love is essential. I can only film someone if I love them.”

“I return to the question: why do you make films? If it’s so people will love you, that’s your right. I just want to love my films — and let audiences decide whether to love them or not.”

Cannes: An Exhausting Screening Between Fatigue and Panic

When he speaks of Life After Siham, his voice grows heavy with emotion. “During the screening in Cannes, I cried. It was in the ACID section, there were four hundred theater owners. It was the third day — everyone was tired.”

He recalled a scene that was meant to be funny: no one laughed. Not a single reaction. “I was sitting there and began to panic. I had opened the doors of my home and invited strangers in — and suddenly, I didn’t want them there anymore. I was crying because for ten years I had worked on this film, it was my baby, and at the same time I felt my mother’s presence with me. But it was over — my mother was gone, and the film no longer belonged to me. I had to accept that it was finished, that I had to say goodbye to a process — like a child turning eighteen, ready to live his own life, to make his own choices.”

He drew a lesson from it: “If your film succeeds, good. If not, you must understand why it failed and learn to do better next time. My first short, which I hated, taught me a lot.”

Youssef Chahine’s Films as Collective Memory and Refuge

He went on to explain how the idea of using clips from Youssef Chahine’s films came about. “I don’t quite remember how I had the idea, but I realized that Chahine’s films are part of our collective memory. By using them, I created a connection between my mother and the audience.”

During the editing, he realized that showing too many photos of his mother would not have the intended effect. “The audience didn’t know her — those images wouldn’t touch them. But everyone knows Chahine’s films. They’re part of our shared subconscious, and those scenes create a link and express emotion.”

He remembered a deeply moving moment: “My mother was very ill. Her mouth was swollen; she had trouble speaking. She said to me: ‘Namir, you once said you’d go to Cannes. But you haven’t made any film that’s gone there yet. If one day you do, know that I’ll be with you, and I’ll wave to you.’”

He and his editor watched that sequence many times, but it was unbearable. “Her face was too swollen. I couldn’t show her like that. I replaced it with Chahine’s footage — it conveyed the same meaning, without showing her diminished.”

Depression, Doubt, and the Need for a Team That Believes in the Film

Life After Siham was not an easy film to make. “After starting the shoot, I went into depression for three years. I thought the film would never be finished.”

It was his editor who pushed him to continue. “He told me: you need a producer and a screenwriter who believe in you.” Namir then met a passionate producer ready to champion the project. “You need someone with perspective, someone who understands your film and supports you.”

Making a personal film, he said, takes strength and patience. “This kind of cinema is difficult, not only artistically but because it forces you to confront yourself. You have to accept being fragile.”

A Man, His Camera, and a Family That Calls Him a Fool

“The subject of the film is a guy who has always been filming his family — always — and his family thinks he’s an idiot. It’s as if the camera has always been his memory. That thread was hard to find. The main character, contrary to what one might think, isn’t Siham — it’s Namir. It’s his story with the camera, stretching back many years before these films even existed.”

In Cairo, before the students, he spoke of this vulnerability with rare candor. “Life After Siham is a painful film, but it’s also full of life. These emotions — we spend our lives trying to avoid them. The film forced me to face them.”

And he concluded simply: “Filming is loving. It’s understanding. It’s saying goodbye without forgetting.”

Rooted Between Egypt and France, Transmitting an Inherited Legacy

Across his three films, Namir Abdel Messeeh has continued to explore the same furrow — that of memory and belonging. By filming his father, his mother, his Egyptian family, his village, and then their memory, he has sought to preserve what might otherwise fade: gestures, voices, faces, the language of a homeland left behind but never lost. His cinema takes root in this inner Egypt, passed down by his parents, which he carries within him, deep in his being, and strives to protect from time, as if afraid his roots might dissolve.

This work of memory is also a way of building himself. French by birth and by life, Egyptian by blood and by heart, he connects these two parts of himself to create a space of passage — a bridge between two histories, two imaginations, two ways of existing. He documents in order to remember, but also to keep the chain unbroken — so that the bond continues to live through images.

And when Life After Siham closes this long chapter of mourning and transmission, one final question lingers in the air: the heritage he has preserved — will he pass it on in turn? Will his children continue this work of memory, this ongoing dialogue between roots and present, between Egypt and France, between life and what it leaves behind?

Neïla Driss