At the 46th Cairo International Film Festival, held from 12 to 21 November 2025, a panel organized in partnership with Coventry University turned its attention to a crucial question: how can the visual heritage of Arab cinema be restored—and preserved—for future generations?

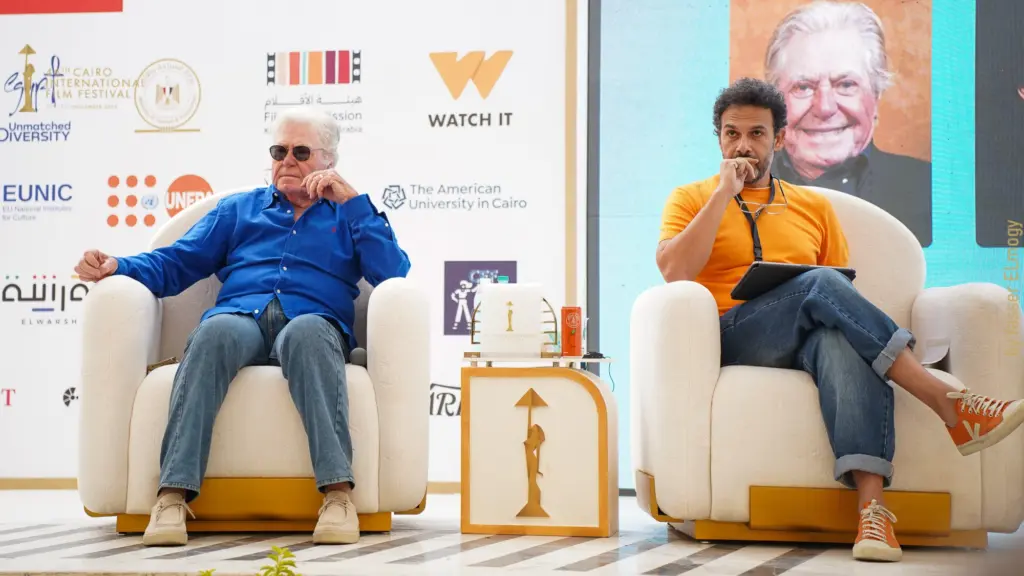

Titled “Restoring the Visual Heritage of Arab Cinema”, the discussion brought together key figures in the field: Hussein Fahmy, Tamer El Said, Ossen El Sawaf and Stefanie Schulte Strathaus, under the moderation of Maggie Morgan. Over the course of nearly ninety minutes, the speakers explored restoration not only as an artistic process, but as a moral duty, a collective endeavour, and a long-term project of preservation and memory. Their exchanges revealed a nuanced and often complex vision of what it means to save the image of Arab cinema.

Hussein Fahmy opened the session by welcoming the audience and expressing gratitude to his team. He highlighted the scale of the effort underway: this year, the CIFF is presenting ten newly restored films, in addition to the ten shown last year—which return due to the strong response they had received from audiences during the 45th edition. Twenty films over two years marks a significant achievement, yet it represents only a fraction of what remains to be done. The institution he represents holds around 1,400 films needing restoration. “It’s a real treasure,” he said, fully aware of the enormous responsibility this entails.

Selecting which films to restore is, he admitted, a challenge in itself. Priorities are set according to artistic significance; he mentioned, for example, the works of Hassan Limam, which must be restored first. Restoration becomes both a choice and a transmission. He also recalled how difficult preservation used to be: film negatives scattered in multiple boxes, stored under strict cold-chain conditions. Today, digitization ensures far greater stability and enables wider access, with English subtitles now added to all restored copies to broaden their reach.

Still, he made one point very clear: “Restoring a film doesn’t simply mean fixing flaws or imperfections.” Restoration, he insisted, is a deeper process that touches the very meaning of a film.

This idea was taken up by Tamer El Said, founder of the Cairo Cinematheque in 2012. Located in the heart of downtown Cairo, the institution has spent more than a decade preserving, restoring and digitizing Egypt’s film archives. For him, the question “Why restore?” deserves real reflection. Egypt possesses vast cinematic archives, and he sees it as essential to make them accessible, to spark new discussions, and to offer young filmmakers the chance to engage with their own heritage. For too many years, he reminded the audience, restoration was done abroad. This is precisely why reclaiming that expertise and “reappropriating our heritage” is so important.

Inside his laboratory, a scanner capable of handling all film formats allows the team to digitize without damaging original materials. They also have a color-grading device, an analogue-film development workshop, and maintain both analogue and digital versions of each film. Strong international networks make it possible to locate missing copies abroad, and collaborations with universities provide constant training opportunities.

For Tamer, restoration must follow strict ethical guidelines. Even though technology can now deliver astonishing image quality—or even colorize older films—he refuses any intervention that alters the essence of the work. “A 1958 film must look like a film from 1958,” he said. Without solid research, restoration can easily distort a filmmaker’s intention. He gave a striking example: while consulting Hussein Sharif’s archives, they discovered that he wanted each scene in one of his films to have a different color palette. Without this document, they might have standardized the tones, completely contradicting the filmmaker’s vision.

This ethical approach underpins the Remastered program, a four-month training initiative involving nine mentors and sixteen trainees—eight specialized in image restoration and eight in sound. Beyond learning the tools, participants worked on understanding artistic intentions, assessing damage and handling original materials with care. A highlight was the participation of a restoration specialist from Bologna—home to one of the world’s leading film restoration centers—who had worked on Shadi Abdel Salam’s The Mummy.

The program led to a collaboration with Misr International to restore four films by Youssef Chahine. Three had already been restored in the past, but not to a standard that preserved their technical and aesthetic integrity. The team is now reworking these restorations entirely while restoring a fourth title as well. Meanwhile, work continues on other iconic films from across the Arab world, including Syrian and Sudanese classics.

The conversation then turned to international collaboration. Why is it so essential, and who actually “owns” the films? Stefanie Schulte Strathaus, from Arsenal – Institut für Film und Videokunst e.V., addressed this directly. She began by questioning her presence on a panel dedicated to Arab cinema, before presenting the living archive she manages, founded in 1963. Arsenal’s collections include films from East and West, from Latin America and beyond. She explained how, during the first edition of the Berlin Film Festival in 1971, Arsenal had begun subtitling films into German to screen them across German-speaking regions. Over time, these copies aged, revealing an urgent need for preservation.

Funding was a problem: available grants were reserved for German archives. International films had no allocated resources. This changed dramatically when a researcher from India, searching for a film she could not find anywhere in her country, eventually located a copy in Arsenal’s archive. This revelation led Arsenal to open its collections, attract new funding, and launch collaborative restoration projects. “It’s not about who owns the film,” she said. “It’s about how we preserve it together.”

The discussion deepened further with the intervention of Ossen El Sawaf from the Jocelyne Saab Association. Founded in 2019, the NGO has worked to restore Saab’s films, many of which had suffered significant damage. He shared a telling anecdote: a foreign technician, proud of his sound restoration work, eventually admitted that he did not understand Arabic. How can one restore sound without understanding the language, the nuances, the meaning? Restoration, he stressed, is not just about cleaning audio—it is about safeguarding ideas, memory and cultural expression.

He also underlined the financial strain: restoring films abroad is extremely expensive, sometimes more costly than producing the film itself. And by sending films overseas, institutions abroad ultimately make preservation decisions according to their own criteria. To counter this, the association focuses on research, personal archives and training. Workshops have been designed to train new restorers who will, in turn, train others. A new workshop is even taking place during this edition of the CIFF.

Their aim is twofold: to restore and to circulate these films. Ossen noted that the archives of Dunia (2005), held at the Cinémathèque française, were in such poor condition that they had become unusable—an alarming reminder of the need to regain control over restoration within the region. A new center will open in Lebanon in 2026, with trained staff. The association hopes to multiply workshops across the Arab world. The Archive Circulation Initiative, created by the association, connects researchers, restorers and institutions, documents restoration processes and helps restored films reach new audiences.

The panel later returned to Egypt with a question for Tamer El Said: how is restoration coordinated locally, and are Arab filmmakers involved? He emphasized the strong spirit of cooperation among archives, film museums and institutions such as Misr International. Their efforts complement those of the CIFF and the Jocelyne Saab Association. But he insisted on the difficulty of research: restoring a film sometimes requires locating copies abroad to determine whether a “flaw” is truly damage—or a deliberate artistic choice. “This is only possible if we understand the filmmaker’s intention,” he said.

The final question touched on colorization: would black-and-white films ever be colorized? Hussein Fahmy was unequivocal: no. If a filmmaker chose black and white, that choice must be respected. “It is our moral duty,” he said. While colorization experiments exist, none have been convincing. What matters most, he insisted, is ensuring that restored films are shown, seen and brought back to life.

As the session drew to a close, a single idea stood out: restoring Arab films is not a technical operation, but an ethical and cultural commitment. It requires research, collaboration and an understanding of memory. It is a gesture of preservation—but also of transmission. And in this patient, collective and deeply intentional work, the visual heritage of Arab cinema finds not only a renewed past, but a future.

At the heart of this effort lies a simple, urgent question: what becomes of this memory if younger generations do not embrace it? These films, revived after years of neglect, are waiting to meet new viewers, to pass on forms, ideas and ways of seeing that shaped earlier eras. Preservation matters only if it sparks curiosity—if it encourages young filmmakers to understand where they come from in order to imagine where they can go. Perhaps this is the essential challenge: to ensure that restored films become not only a legacy, but a starting point—a call to learn, to question, to create, and above all to watch these works so they may live again.

Neïla Driss