Tunis Hebdo | Since a certain “January 14”, President Habib Bourguiba has become the star of bookstores and the darling of authors and listeners. The “Revolution” has, in fact, released the “Zaïm” from the silence in which it had locked him up, since a certain “November 7”, and even after the death of “El Moujahid al Akbar”, a certain Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. And suddenly, the languages were untied and the feathers were unleashed to provide readers, Burgundian or not, works sometimes apological and admiring, sometimes critical and more nuanced.

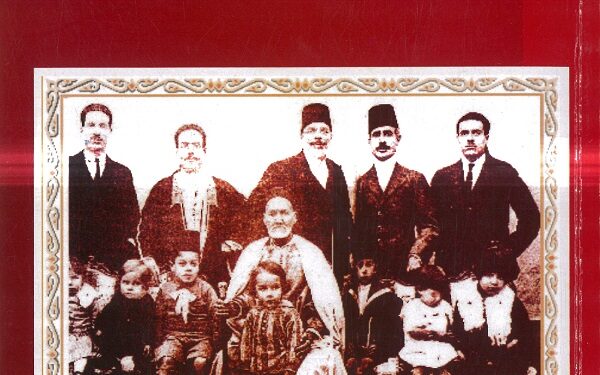

Bourguiba brothers

The latest book, after the resurrection of Bourguiba, we owe it to Moncef Charfeddine, a great specialist in the Tunisian theater and its history, cultural journalist, radio and television producer, ex-Professor of Arabic, ex-premier responsible for the theater within the Ministry of Cultural Affairs between 1964 and 1967, and the list of professional and cultural activities of Si Moncef can be more so, who is 88 years old (“Mazalet El Barka”, if Moncef!), Gave for culture and the press, but for the theater in the first place.

Now that we know the author a little bit, we will understand why his book on “Raïs” carries the title of “Bourguiba, his brothers, theater, culture and other subjects”. The subject will therefore be focused on theater and culture. But the brothers of Bourguiba, would you say? No, it is not a “off-topic” when we know that three of the brothers of Habib Bourguiba, in this case Mohamed, M’hamed and Mahmoud had with the theater more than solid links.

But, it is the elder, Mohamed Bourguiba (1881-1930) who, between his brothers, will remain the most famous in the history of the Tunisian theater. After taking part in 1908 in the (aborted) project of the first theatrical association with a hundred percent Tunisian, “enejma”, he was one of the first Tunisians to go on stage, on the occasion of a play (“Nadim or sincere fraternity”) presented, in May 1909, by the “Egyptian-Tunisian troupe” (Al Jaw Al Masri Attounsi).

M’hamed Bourguiba (1894-1953) was, for his part, the theater manager, and adhered to several theatrical associations, while Mahmoud Bourguiba (1896-1952), who should not be confused with the “poet of youth” who bore the same and names, in the wake of his brother Mohamed, translated or adapted, for the latter, Classic repertoire.

A family passion

So, Habib Bourguiba was born and grew in an environment where the theater was a family passion. His love for the theater, to which the second part of Moncefddine’s book will be consecrated, therefore has a first explanation. His studies in Tunis and his contact with the world of theater, through his brother Mohamed, made the rest of the future president of Tunisia who had the opportunity to be a replacement, to set up a play in Monastir, to which he invited Habiba M’SIKA to play the first female role.

In Paris, he did not cease, thanks to the half-variety from which he benefited as a student, to frequent the theater rooms, to admire the masterpieces of the classical repertoire. Upon his return to Tunis, he contributed from time to time to the theatrical chronicle of “Tunisian action”, the organ of the neo-Destour.

This passion for the theater, Bourguiba will implement it as soon as it is at the head of power, after the independence of the country. His famous speech on the theater (November 7, 1962) constitutes, to this day, a real program for the development of the fourth art, and he was, during the life of Bourguiba, the guide and the reference of cultural policies in matters of theater.

From this pre-program discourse, fully reported by Moncef Charfeddine in his Arab and French versions, were born the great achievements of the Tunisian theater in which the author took part as director of the theater service at the Ministry of Cultural Affairs and Information: theater week, school theater, regional troops …

And there, we see Moncef Charfeddine transforming into a direct witness, even an actor in the history of the theater, with, in support, a well-supplied documentation concerning all these achievements, after having been, in the first part of the book, a rather distant historian, leaving the floor to the witnesses of the time, and to Habib Bourguiba himself, first, through his conferences at IPSI in particular.

Vice-president of Hope

In the third and last part, Moncef Charfeddine is rather chronicler, inviting us to an “supplement” of various subjects where seriousness is disputed to the more or less light anecdote: the place of Sadiki in the formation of Bourguiba, his first trip to France in 1923, his vice-president of Hope, his small size, his imitators, the story of his own coffin. Bonus, interviews with Bourguiba, poems in his name Mage and a reminder of stamps bearing his effigy and certain works devoted to him.

A total of 430 pages where the author’s text is, as in documentary cinema or on television, interspersed with documents of all kinds: photos, press articles, official speeches, ministerial circulars. A bushy set where Arabic and French are mixed, and which has the advantage of being able to be read in the order or menu that the reader will choose.

The book, with all this documentation, is from the album and the archive at the same time, but if there is a guiding thread in all this material it is the love of Moncef Charfeddine, like that of Habib Bourguiba, for the theater. And we see through the book how the author and his (real) character come across through the theater in particular: they have the same love for the fourth art, but the circumstances put them in contact more than once, in Tunis, Sousse, Sfax or in Paris, before and after independence, and in different statutes: militant Bourguiba and head of state, Moncef Charfeddine student, amateur and practicing theater,

Bourguiba-Charfeddine: same fight?

And we feel, by leaving the reading of this work, that in parallel with the life of Bourguiba, it is also the life and the work of Si Moncef, in all its litters relating to the theater, which parade before our eyes … Habib Bourguiba-Moncef Charfeddine: same love for the theater, same fight? Yes, it must be said, even if, by humility, if Moncef would not admit, perhaps.

Adel Lahmar