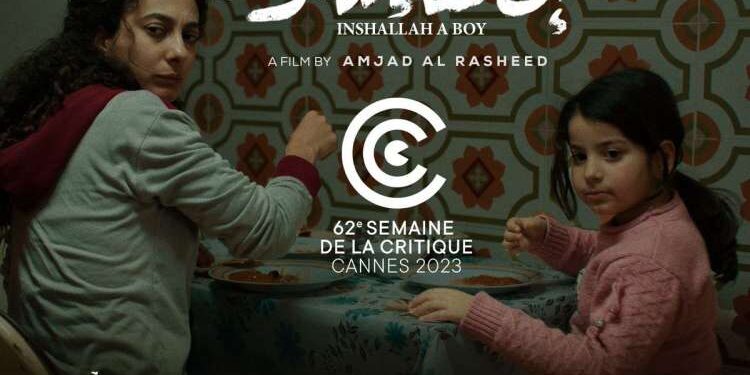

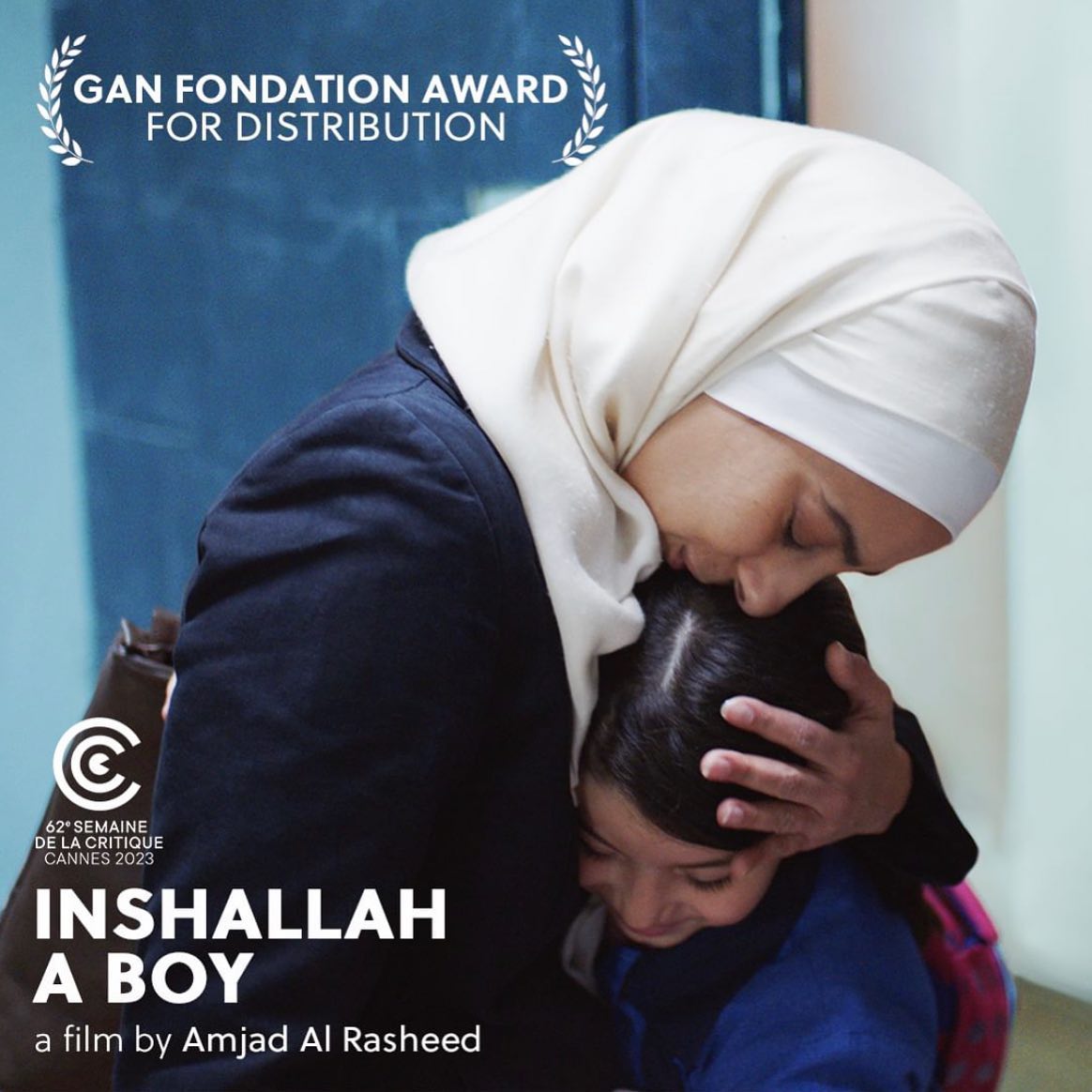

The Jordanian director Amjad Al Rasheed marked the Jordanian cinematographic history with his first feature film, “Inshallah a Boy”, which made his first in the critic week during the 76th edition of the Cannes Festival, as the first Jordanian film to be selected at the Cannes Film Festival, all sections. The film has also won the Gan Foundation Prize for broadcasting.

Amjad Al Rasheed, born in 1985 and holder of a master’s degree in realization and assembly, quickly established itself as one of the emerging talents in the region. In 2016, it was recognized by “Screen International” among the five “Arab Stars of Tomorrow (the Arab stars of tomorrow)”. His participation in the Talent Campus of the 57th Berlinale was the prelude to a series of acclaimed short films in various Arab and international festivals.

Synopsis:

Jordan, nowadays. After the death of her husband, Nawal (Mouna Hawa), the thirties, must fight for what she considers to be the heritage of her only daughter, in a region of the world where having a son changes everything.

Inshallah a boy Carries the spectator to contemporary Jordan, offering an emotional dive into the life of Nawal, a woman in their thirties, faced with a monumental challenge after the loss of her husband. The film denounces the brutal consequences of inheritance laws based on shariaa.

From the end of mourning ceremonies (fark), the dark face of the paternal uncle (Haitham Omari), initially compassionate, is revealed. This greedy predator will start by demanding that Nawal reimburse her a debt from her husband of which she has never been informed (he nevertheless produces no evidence, the widow having to settle for her simple word). Ignoring the need to leave Nawal time to do his accounts, he also presss it to receive his share of inheritance, which comes down to a partially paid pick-up and a small family apartment occupied by Nawal and his daughter, Insensitive to the fact that they may find themselves on the street and not taking into account the substantial financial contribution of Nawal to the purchase of this family apartment. A legal proceedings are also quickly started by this paternal uncle impatient to harvest his share of the heritage of his brother.

The patriarchal dimension of the inheritance laws, governed by shariaa, is highlighted: among the Sunnis, when there is no male descendant, a only daughter can inherit only half of the heritage of her father, the other half returning to the parents of the paternal family. Sometimes, moreover, these relatives of the paternal family disappear as soon as they have touched their share and no longer worry about their niece. Muslim societies abound stories of these girls who lose financial security after the death of their father and who can even find themselves on the street after having lived in a certain comfort, victims of the betrayal of their loved ones.

If Nawal had had a son, the rules would therefore have been different, but the current reality is that of a woman having to fight against the greed of the uncle, indifferent to his situation and that of his daughter. Pressure intensifies with threats and legal proceedings aimed at taking custody of the small niece.

The film exhibits the discrepancy of laws inherited from Shariaa, however still in force in the vast majority of Muslim countries, with contemporary reality. The rules designed fourteen centuries ago, justified at the time by the traditional economic role of men, prove to be unfair today since women are educated and educated, that they work and contribute financially to family expenses, defying the need for male guardianship.

To escape this invasive uncle, Nawal hopes and claims that she is pregnant, hoping to escape the inequitable distribution of heritage if she gives birth to a boy.

By exposing social injustices, Inshallah a boy Is not limited to the criticism of the estate laws, but also explores other facets of the oppression of women, such as the very fragile right of care of mothers, the “modesty” imposed on women, both in their behavior and their clothing (veil and long clothes), the right to abortion and the ban on sex outside marriage. These themes extend the scope of the story beyond the legal sphere, plunging into the cultural and religious norms which affect the daily life of Jordanian women, whether Muslim or Christian.

The film acquires significant importance by exposing the reality of unjust laws, inviting the public to immerse themselves in the perspectives of Nawal and to question the validity of obsolete traditions. Nawal’s ordinary life, suddenly upset by mourning and the threatening of losing his inheritance, raises fundamental questions about the fairness and predisposition of uncles to exploit the death of their brother as if they were impatiently awaiting this death.

Inshallah a boy presents itself as an elegant thriller, awakening questions without offering definitive answers. The mysteries, such as the locked phone belonging to Adnan, of which Nawal cannot guess the password, the condoms discovered in her jacket, her dismissal of which she had never heard, the shady behavior of the secretary of the previous office of Adnan, as well as the malicious reason, or perhaps simply reckless, for which he never signed the contract recognizing the financial participation of Nawal Two owners in part in joint possession, add a layer of complexity. These elements encourage spectators to reflect on the subtleties of the human condition.

This captivating story, anchored in the moving performance of Nawal, captivates the spectator from the first images. The transformation of this woman, from vulnerability to resilience, becomes a powerful metaphor for the fight against systemic injustice. Through the course of the story, Nawal gradually emerges as a figure of force in the face of adversity. At the beginning of the film, when her bra is falling into the street, she backs up in her balcony to hide in shame, when during the mourning ceremony (fark), she is led by the lady in niqab which reminds her of her “homework” of widow, she is silent. But thereafter, she takes over her destiny, looking for solutions in a complex and hostile environment. Nawal embodies a strong and determined female figure, defying oppressive social norms.

Inshallah a boy Thus is part of a cinematographic work of considerable importance, denouncing unjust laws and offering a deep reflection on the female condition in an evolving society. The remarkable performance of Nawal and the sensitive staging of Amjad Al Rasheed make this film much more than a simple entertainment; It is a call for action, a poignant exploration of the universal quest for justice in a world sometimes hampered by outdated traditions. This poignant work plunges into the complex cogs of a society where ancient laws collide with modern reality. Amjad al Rasheed offers a deep perspective on the challenges that women face in this region of the world, highlighting persistent inequalities and archaisms that remain despite the evolution of time.

These two works, and others, show that it is high time that Muslim countries are working to repeal these archaic, retrograde and unjust laws and comply with the current reality and the equality of women and men. Tunisia started this work several years ago, but unfortunately it stopped along the way, still promoting today in 2023, men on women and by continuing this flagrant injustice which hurts so much and generates many sufferings. Today, not only should men and women be equal to all legislative rules, including estate, but even more, it would be necessary that when a person with children dies, only these children and the surviving spouse inherit, all other members of the family should be dismissed.

Neïla Driss