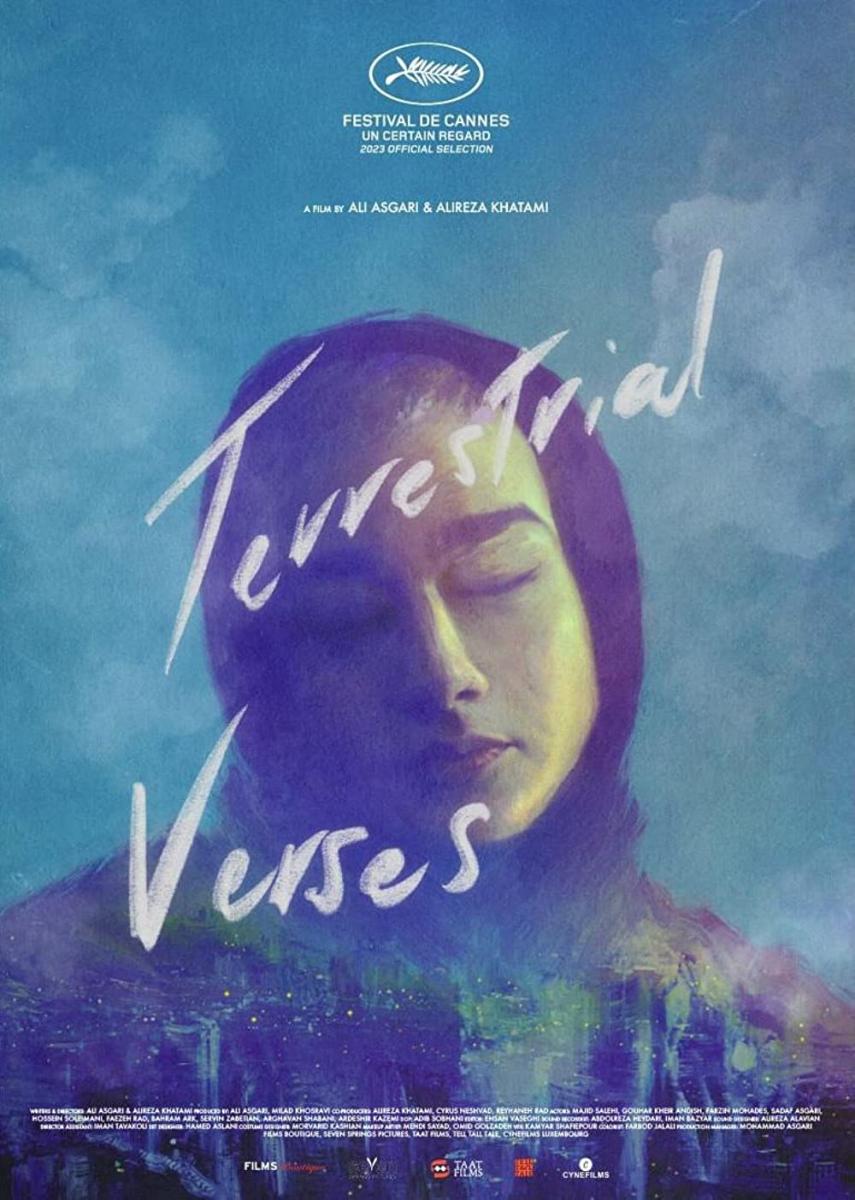

Cannes 2023 – presented in the Un certain Look section, “Terresrial Pours” (Chronicles of Tehran), produced by Ali Asgari and Alireza Khatami, touches by his simplicity, his accuracy and the echo he arouses in us, having sometimes experienced some of the situations presented.

Before the screening, the directors briefly presented the film: ” What happened in Iran 9 months ago made Iran’s history can be divided in before and after. This does not mean that before there was no resistance, there were decades of resistance, but what made September 2022 special is that there was a moment that crystallized this resistance, a moment of hope (…). In Iranian poetry, there is a technique called “mounadhara”, which means debate, where the characters engage a debate. This form of dialogue fascinated us. We need dialogue, more than ever, a dialogue that brings together and unit. How to bring this form to the cinema? We made this film with other friends and we thought that maybe you will hear us. We invite you to see it, to listen to the stories, we hope that you can think with them, and that you will smile, even laugh, because nothing legitimizes the absurdity of oppression. »»

Through nine shorts sketches, the directors present the daily life of the Iranians by staging women, men and children in apparently banal moments, where the absurd is disturbing everything. Each of these characters is the hero of a sketch, introduced by a title card comprising his first name, turned into a fixed sequence, during a conversation with an anonymous interlocutor, which one never sees, but which speaks of an authoritarian and severe voice. In several cases, this “voice” represents the bureaucratic and inquisitive government: for example, an official who issues driving licenses roughly questions the citizen about his tattoos, deeming them abnormal and almost immoral, a police officer criticizes a young woman for driving his car without a veil to hide her hair, a civilian civil servant who records births reproaches the citizen the chosen first, etc.

All these sketches have one thing in common: they show the worst absurdities caused by the deprivation of freedom in Iran: not having the right to choose the first name of your own child, not having the right to go out without a veil, not having the right to dispose freely of your own body, not having the right not to practice your religion, not having the right to write what you want, not to have the right to choose the theme of your own film, etc.

The Sketch of the little schoolgirl is particularly shocking. In Iran, all girls/women are forced to veil themselves from the age of 7 years. So we see a little girl in a store, jogging, a helmet on the ears, sketching dance steps. Then, as she reached age and she will join the school, her mother must buy her the right clothes. Following the advice of the saleswoman, this joyful child will turn into a gray and sad ghost. Jogging is covered with a dull and long coat, the hair is hidden by a covering veil, the whole is covered with Chador. The little girl is nothing more than the shadow of herself.

Same for the scriptwriter’s sketch who sees his script gradually sausage. Severe and illogical censorship, oppressive censorship. The censor does not want to understand anything, you have to cut there, and there, and again there. History no longer makes sense? It doesn’t matter, it can be changed. Exasperated, the scriptwriter proposes to write a film by scrupulously following facts told by Koranic verses, but the censor still disapproves of them and still cuts this again.

We also notice a progression in the age of the characters: a newborn baby, a child, a high school student, a young adult, and so on to an old man. This progression skillfully symbolizes that an Iranian is deprived of his freedoms throughout his life, from birth to his old age, and that he can never live freely. It is an extremely dark and sad theme, and the two filmmakers illustrate it with a form rarely seen in the cinema. During each sequence plan, the discussion is only shown from the character’s point of view, and the interlocutor is never visible. The directors thus show the coldness and the absence of empathy of the Iranian society, the worst here is depicted. And the comments of the interlocutor are each time raging violence. It is not difficult to imagine the Iranian people revolt when such scenes of humiliation are part of their daily life. Moreover, all these little stories are inspired by real testimonies, as Ali Asgari and Alireza Khatami said before the projection in Cannes. And we can easily believe them, because such situations can also present themselves in our Arab-Muslim countries.

What hurts is that some of these sketches could also concern Tunisians, from the first, who shows a father who wants to name his son David, but is refused this choice because it is a “Western” first name, in other words non -Muslim. Or the job interview sketch, where the employer, apparently perfect, turns out to be a harasser. Or the civil servant who mixes with private, even intimate life, people, or another who poses indiscreet questions about religious practice. In the name of what? By what right do they interfere in the privacy of individuals? When will we learn in our countries to respect the private sphere of each citizen?

Since September 2022, Iranians have been fighting tirelessly to try to conquer some of these rights and freedoms, even elementary. Each act and gesture counts.

Actress Sadaf Asgari, present at the first, wore a short dress and was not veiled. Asked, she confirmed that she lived in Iran. Wasn’t she fearing the reprisals on his return? If she confirmed. By getting dressed in this way, she even endangered her life. But it’s worth it, she added.

What an example of courage on the part of these Iranian women !!!

Neïla Driss