He will have spent his life loudly what others whispered, and to make a sweet, lucid, ironic anger, but always desperately human on stage and on stage. Ziad Rahbani died this Saturday, July 26, 2025, at the age of 69, leaving an orphans of entire generations for whom his words, his melodies and his silences were part of a collective, painful and beautiful memory at the same time.

Heir to a mythical family – he was the son of the Grande Fairuz and the composer Assi Rahbani, member of the legendary duo of the Rahbani brothers – Ziad traced a singular path from his beginnings. And if he grew up in the shade of an immense tree, he never wanted to shelter. Very early on, he posed as a counterpoint. At 17, he made up his first work for musical Al Mahattainterpreted by his mother. But it was in 1974 that the Lebanese public really discovered his voice, with Nazl El-Souroursatirical piece, funny and desperate, where he plays a disillusioned character in a country already on the edge of the abyss. The following year, the civil war broke out. It will last fifteen years.

It is in this tattered Lebanon that the work of Ziad Rahbani takes all his strength. Bennesbeh Labokra Chou? (What about tomorrow?) is undoubtedly one of his most striking pieces. It stages left-handed, in a bar, in Beirut. Simple characters, united by loneliness, fear, alcohol and black humor. All punctuated by the music of Ziad, melancholic, jazzy, always on the edge of implosion. It is a popular, but deep theater. Committed, but never didactic. A theater that does not give a lesson, but tends a mirror, cruel and tender at the same time.

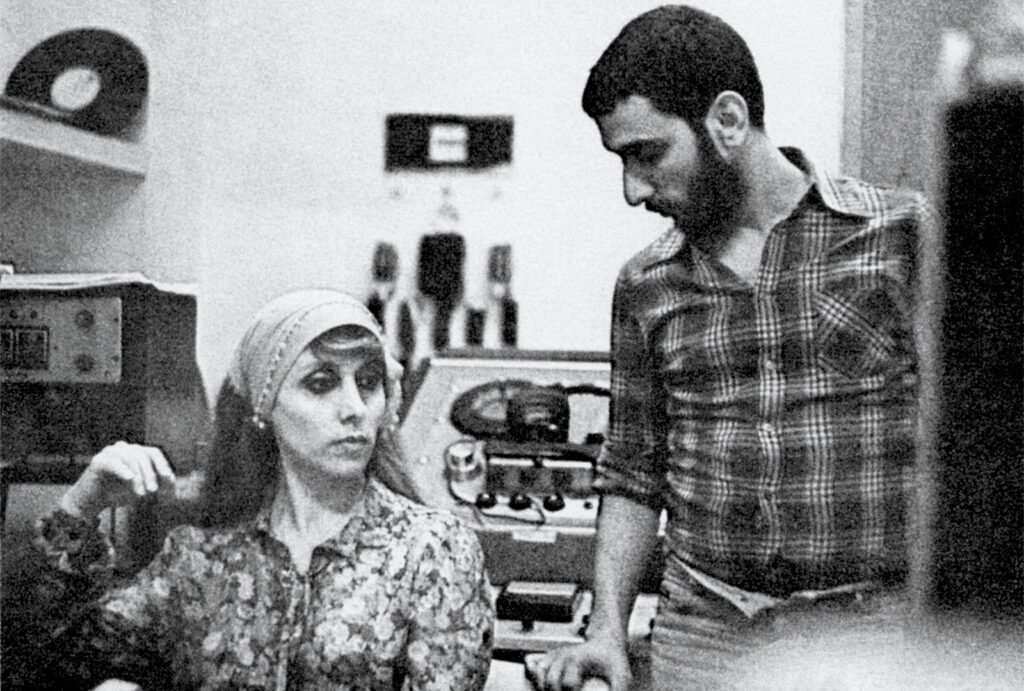

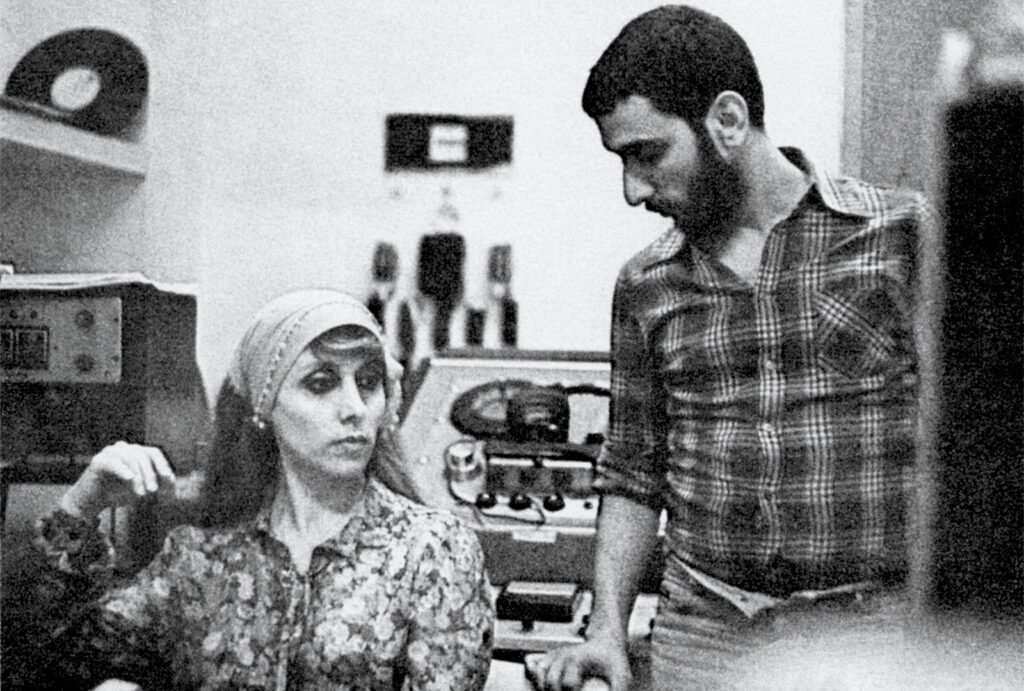

As the years go by, Ziad Rahbani continues to write, compose, play. He invents a hybrid musical language, at the crossroads of jazz, funk, Western classic and Arab modes. He is not trying to please, he seeks to say. He refuses ease, is wary of success. He makes up overwhelming songs for Fairuz – Opening 83,, Kifak Inta,, Bala wala chi – which decide with the large lyrical frescoes of the Rahbani brothers. It is a more intimate, harsher, sometimes even rough turn. Fairuz, usually ethereal, becomes an injured, worried, questioning woman there. An even more human singer.

And yet, despite this powerful collaboration, their mother-son relationship has experienced gray areas. For several years, they did not speak publicly on each other, and their common presence on stage has become scarce. Their personal disagreements, their very different life choices, have fueled tensions – sometimes exposed, sometimes simply guessed. But these private silences have never altered the depth of their artistic link.

Between them, there was never an artistic break. Despite the silences, leaks, tensions, their musical bond remained intact, underground, unwavering. Fairuz carried him as a child, he brought it back on stage. He knew his smallest silences, his breaths, his anxieties. She was her first world, he was a new voice for her. Their dialogue, through music, continued well after the words were rare. He made up for her not what she wanted to hear, but what he knew she could wear – with this injured, almost painful grace, that only Fairuz could offer to the Arab public.

Ziad Rahbani has never rejected oriental music. He jostled her, interviewed, moved. To those who saw in his love of jazz or funk a betrayal of traditions, he responded with writing. In its compositions, the oud cohabits with the electric piano, the derbouka slips between two lines of bass syncopated, and the oriental improvisations find an echo in the flights of the saxophone. It was in a parentage, but without nostalgia. He recognized the debt towards Sayyed Darwich, Mohamed Abdelwahab or the traditional maqâms, while opening other paths to them. In reality, he made Arab music what she has always been: a living, open art, in conversation with the world.

Ziad Rahbani has never limited himself to the scene or the studio. Man of radio, he provokes, quips, deconstructs. A assumed communist, claimed atheist, he stands away from political institutions as well as religious powers. It embodies a form of counter-culture, rare in the Arab world. He speaks the language of the people, with its roughness, their faults, their raw humor. He is mocked, criticized, sometimes censored, but loved. Immensely.

His political commitment is not reflected in slogans, but in a vision. That of a Lebanon that could have been. A lawyer, progressive, egalitarian. This Lebanon has never existed only in its pieces, its records, its illusions. But he dreamed so strong that he became real, at least the time of a show, a song, an agreement.

The announcement of his death caused a wave of emotion in all the Arab world. Lebanese president Joseph Aoun paid tribute to him, greeting a ” cultural phenomenon “,” a rebellious voice against injustice “,” a lucid conscience “. Social networks have filled with personal memories, sentences of his pieces that have become proverbial, so -called bassy songs, like secular prayers so as not to sink.

But Ziad Rahbani would probably not have liked to be sacred. He who, all his life, fought against the frozen icons, the dusty statues, the stifling myths. He preferred irony to reverence, doubt to certainty. In Bennesbeh Labokra Chou?his character launched: “ They say that tomorrow will be better … But today, who takes care of it? This bitter and lucid sentence perhaps sums up all his work.

Ziad Rahbani leaves behind a monumental work, but above all a spirit. That of a free man, painfully free, who preferred the truth to glory, the complexity of simplification, music to propaganda. He was not trying to please. He sought to understand, to feel, to denounce, to exist. Through his words, his notes, his silences.

Today, Lebanon mourns an artist. But more, it cries a consciousness. A voice that, even when she was silent, said something essential. And whose echo, for a long time, will resonate between the cracked walls of a country which he loved so much – in his own way.

Neïla Driss